A Reflection on Reflection

For people who live their lives according to the academic calendar, summer vacation is our “New Year.” This year one of my “New Years Resolutions” was to write more frequently. Writing focuses my mind, and the specificity required to write about music is a frustrating challenge. I want to use my blog to describe and clarify valuable experiences, and use those reflections to support creative works in process. I thought I’d begin with an ode to reflection, the perhaps the most valuable part of my own creative work.

My students at the University of Kansas have all sorts of amazing musical experiences. Some of these take the form of slow, hard earned epiphanies. Others, though, are rapid fire “epoofanies” (a tiny epiphany): a comment in a percussion group coaching, the way a guest artist inflects a melodic line, a composer’s choice of adjective, or the sudden burst of adrenaline from that first perfect four stroke ruff. This all in one day! Unfortunately, we’re all busy. How do we continue to grow when the growing experiences seem to come too quickly to process in the moment?

For me, the answer has always been reflection. This idea that we do not truly learn something until we both experience it and reflect upon it is a significant part of my teaching, and a tremendous part of my personal learning.

Simply put,

Learning = Experience+Reflection

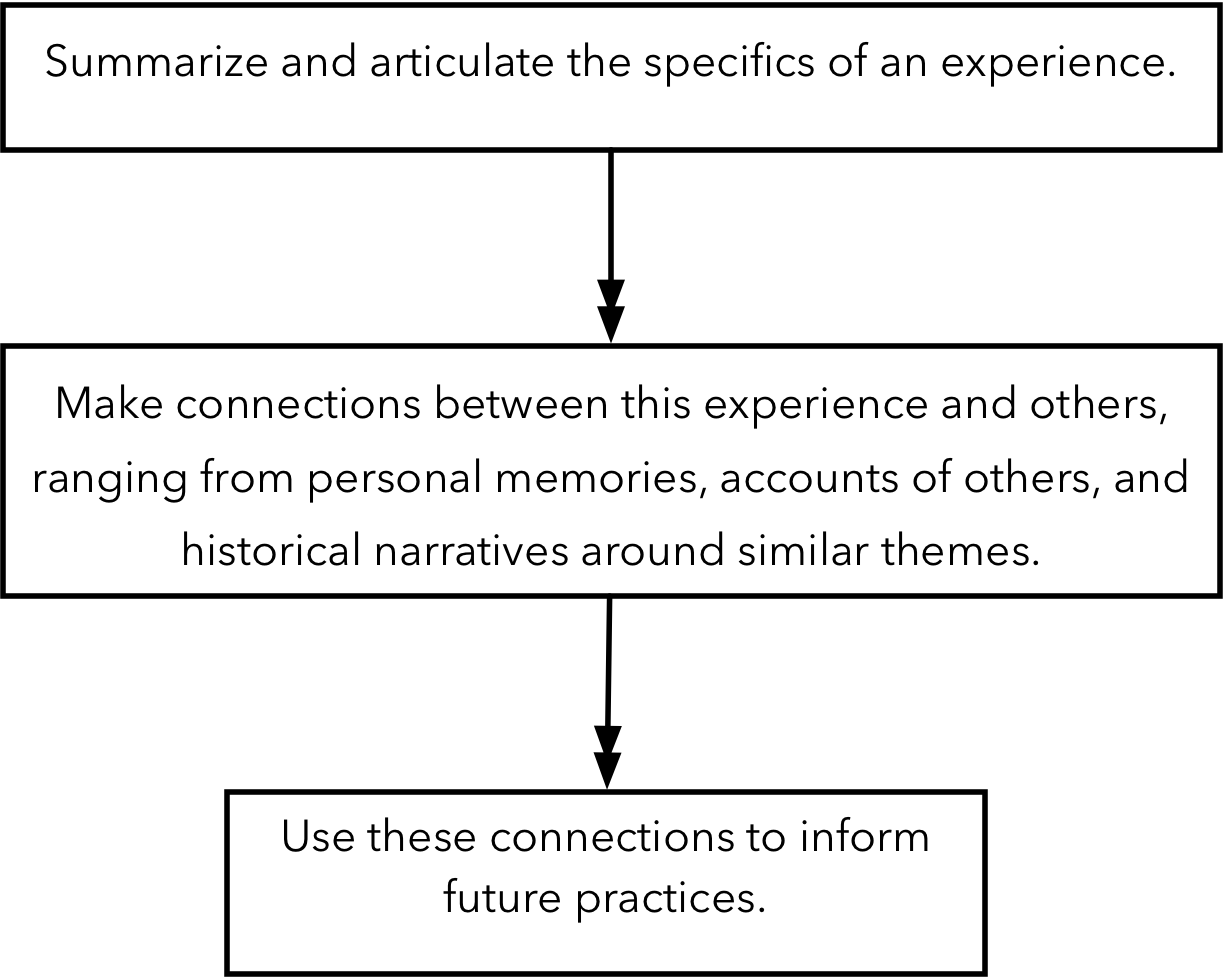

Reflection involves articulating the specifics of an experience, making thematic observations, and connecting these experiences to broader contexts.

A Sample Reflective Process:

I’m hoping to use specific examples from my own projects to unfold these ideas in future writing. For now, I want to focus on what reflection can do for performers, and why taking time to assess and articulate our experiences can inform works in progress.

What

Habitual Journaler Doogie Howser uses reflection to trigger an epiphany.

I taped almost every lesson I took during my undergraduate degree (“nerd!”). Even though I took copious (and, it turns out, illegible) notes during lessons, my written summaries of lesson recordings—typically made the same day or one day after—were more coherent and cogent. Reflection for me was and is a journey that begins with refined summary and deliberate mental organization. (Mine include frequent outlining, lots of charts, an occasional Ven diagram). I can’t understand a concept unless I’m able to re-articulate the essential elements of its argument in my own words. In college, I double-majored in History, and much of my work understanding voluminous, semi-interesting tomes lay in creating an outline, distilling an author’s arguments and re-articulating them in my own words.

Why

This style of reflection, focused on careful distillation and not transcription (I’m no Pierre Menard), is a terrific way to draw parallels with other experiences and develop critical thinking. Reflecting on a masterclass you attended could allow you to work out a larger idea about music from a specific insight describing the problems encountered in learning a marimba solo could remind you of a great practice technique your teacher might have mentioned in your lesson in a class years ago. Reflection can CREATE epiphanies. Just look at master detective Hercule Poirot, who reflects upon his observations during a case, draws connections between the cast of rogues which inevitably surrounds him, and crafts well timed epiphanies:

A point of inflection for KU students. Hope they reflected!

For performers, frequent reflection on rehearsals, lessons, practice sessions, etc focus longterm projects by helping us articulate major themes amidst the daily weed-whacking of practice. In February, KU was lucky to host a masterclass from MET timpanist Jason Haaheim (BTW, check out his blog), and during his information-packed presentation I reflected of the power of reflection in learning maximization (I promise I was paying attention!). I loved his insight that an astute learner brings their teacher problems to solve, not mysteries to diagnose, and that a single lesson should take creative student weeks to fully actionize. Jason highlighted the importance of immediate and focused feedback in the practice room and long-term tracking at the computer in learning and retaining new information. I would add that prose is also a valuable technique for analyzing progress within the practice room, a helpful change of medium that might jostle free some revelatory observations.

Reflection also allows us to work towards not making the same mistakes twice. Recently, I’ve been trying to use Carol Dweck’s notion of the growth mindset to dispel my anxieties and calm negative self-talk. (Productivity guru Astrid Baumgartner has a great summary of Dweck’s writing as it applies to practicing musicians). While I look forward to unpacking those ideas more fully in the coming months, I was struck by the degree to which a growth mindset can be enabled and reinforced through reflection. Reflection serves as reframing, as positive empowerment. “I did more than I thought! I’m not at my goal yet, but I’m taking steps to get there.” At the same time, reflection is a way for critically thinking artists to evaluate and keep tabs on their process.

This notion that a dialogue between action and reflection can empower creativity is especially important to those of us who struggle with doubt and indecision. Self doubt is a constant in my artistic projects; always lurking, but rarely articulated, a silent partner to the types of projects I aspire to as a percussionist, educator, collaborator, and curator. Because of this, I’m resolving to be more public with my own reflections with the hope that they will serve as a counterbalance to the cloudy glaucoma of doubt and keep me rolling. Perhaps by publicizing what’s on my plate and reflecting publicly (although, let’s be honest…) on how the issues could be emblematic or representative of the kinds of wonderful creative collaborations happening all around the world, I can empower myself to think more clearly about my own artistic practice and agitate my little grey cells.