Recording in the Practice Room

This semester at ASU, I’m presenting on a number of skills that successful musicians should have.

We’ve been talking as an institution about how recording oneself has become an essential skill for 21st century musicians. At the same time, I’ve been thinking about how to teach good practice and time-management habits. These concepts meet in on the issue of recording oneself in the practice room, so I am sharing some thoughts below about how I use recording in my practice.

Why Record Yourself?

As I’ve discussed in a previous post, learning is a combination of experience and reflection. Recording jumpstarts this process by allowing the experience to be observed from a number of perspectives without worrying about time, which allows for a more nuanced, critical reflection. More experience + more reflection = more learning!

Similarly, recording provides instantaneous, unbiased feedback about your playing. One of the central tenants of both Deliberate Practice and Design Thinking is that learning requires feedback. With recording, feedback is immediate, and unbound to our biases about our playing. When we learn, we struggle when presented with what David Epstein calls “wicked” learning environments: situations in which feedback is not immediate and in which previous experiences do not imply a future strategy. Because of its immediacy and objectivity , recording oneself in effect turns a ”wicked” learning environment into a ”kind” learning environment.

How? Recording aids in the development of mental representation around our playing, and is like having a teacher in the room with you. In Peak, Anders Ericsson explains that a mental representation is “a mental structure that corresponds to an object, an idea, a collection of information, or anything else, concrete or abstract, that the brain is thinking about.” Thus, “the main thing that sets experts apart from the rest of us is that their years of practice have changed the neural circuitry in their brains to produce highly specialized mental representations, which in turn make possible the incredible memory, pattern recognition, problem solving, and other sorts of advanced abilities needed to excel in their particular specialties.” When we record ourselves during practice, we supercharge that developmental process.

Recording also meshes nicely with the problem solving strategies espoused within Design Thinking, which prioritizes brainstorming many ideas and quickly testing them. Recording is perfect for these tandem processes of ideation and prototyping.

How I use recordings differently than some of my colleagues

My philosophy around recording myself differs from a “pure” application of Deliberate Practice. While Deliberate Practice has as its stated goal the refinement of a narrow band of outcomes (“this is the way”), buttressed by a guru and a clearly-defined learning modality, I prefer to use the tools of Deliberate Practice to achieve the skills of generalization, flexibility, and creativity. Deliberate Practice is both a technique and a philosophy. I prefer the technical elements, but want to avoid the implication that our end goal is perfection of a single performance practice.

My musical goal is to be able to play everything in myriad different manners, and so I use my recording to help develop maximal flexibility. Why is flexibility better than honing one way? In Range, David Epstein demonstrates that those with extreme domain specific knowledge and narrow bands of pattern recognition can’t adapt to new situations. And since you’re going to be working with lots of people who will ask you to change things ASAP to get $$, flexibility seems a valuable and pertinent skill.

What You Need

Good Quality Audio In and Out

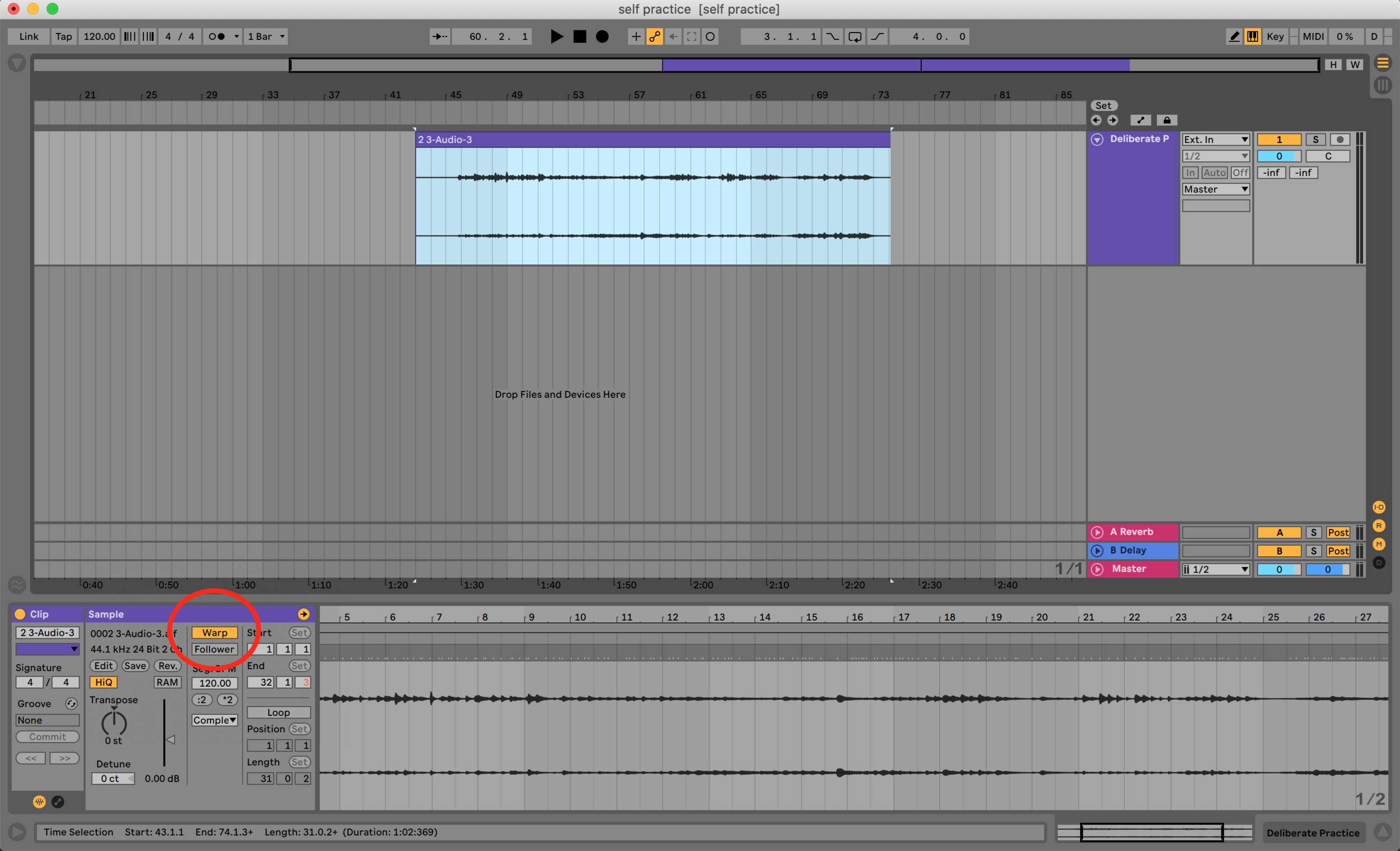

My setup is stereo mics with audio interface and either Logic or Live. I prefer recording into software rather than to a standalone recorder because I like being able to quickly edit audio, loop passages, and compare against previous recordings while using visual and software inspection of waveforms as a quick check of my precision and consistency. On the road, I typically use a Zoom H4 or H6 for quick and dirty recordings. USB microphones are terrific these days, and the plug and play element is very helpful. Make sure you allow plenty of cable length to get a good sound from your sofa—I mean marimba. Personal preference is salient in DAW choice, so try a few out and see what works for you. I use a combination of Live and Logic: Logic because I’m comfortable with the interface for recording and editing, and Live for the ease of changing the tempo of my recordings.

If the goal of our practice is to refine and develop our sound concept, we need good output as well as input. Either good headphones or good monitor speakers can help you make quality decisions about your sound.

Peabody’s list of recommended equipment is a good jumping off point if you’re just getting started.

The Ability to Slow the Recording Down

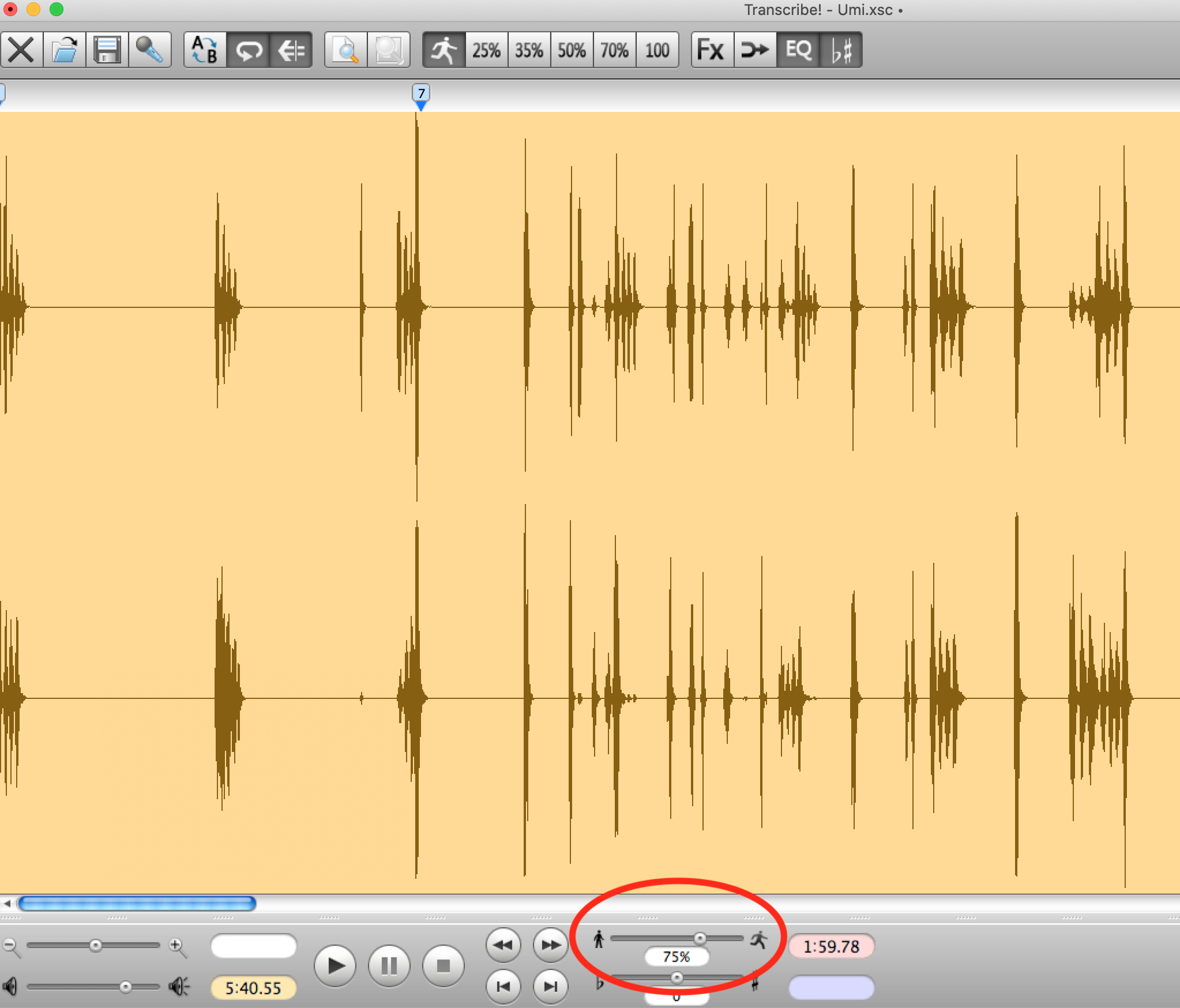

I like to slow down my recordings to more accurately assess issues. Although most DAWs can change tempo without impacting pitch, Ableton Live’s warping feature is perfect for real-time adjustments. Transcribe! works wonders as well, although importing sound files into the program can be just slow enough to discourage me from using it.

Notebook/Practice Journal

I use a notebook (well, a OneNote notebook, sorry Todd Meehan), to keep track of my notes, and to make assignments for myself. I tag assignments and then periodically review and summarize my goals so that I can always enter the practice room knowing what I need to accomplish.

Why no Video?

I typically record audio only in my practice sessions. Why? Video can lead to unnecessary bias. We have a tendency to listen with our eyes, saying that a passage sounds a certain way because it looks a certain way. It opens the door for dogma, and it’s a slippery slope towards the kind of narrow-banded thinking which cripples specialists. That kind of subjectivity is the opposite of what we’re trying to achieve when we record ourselves.

Finally, working with video is incrementally more challenging than working with audio. Video files are slightly more challenging to edit, and the larger file sizes are moderately more annoying to manage. ”Moderately more” is enough to discourage me from recording (I read Nudge, didn’t you?), so I keep things to audio unless I’m working with larger chunks.

Recording Situations

Lessons

Goals: documentation, reflection, synthesis, goal-setting

In a lesson, we pay close attention to our teacher’s words and actions. We throw ourselves into trying things in new, uncomfortable ways. Great teachers are masters at pacing, so after a terrific lesson we might not remember everything that happened. That’s where recording comes in. Students who record lessons improve exponentially.

How-To

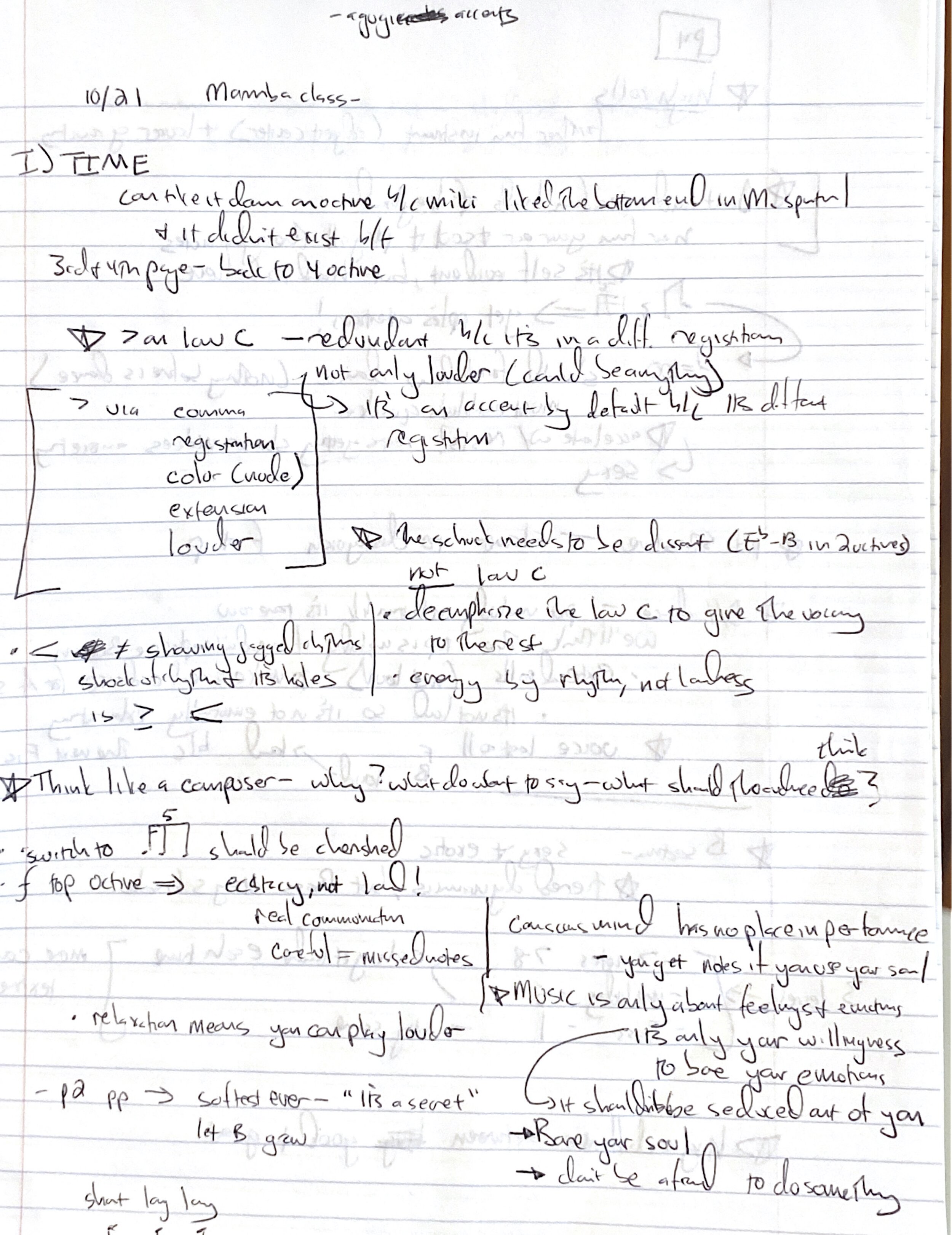

After asking your teacher if you might record your lesson, record the lesson. Then, get to work. My philosophy on lesson recordings aligns closely with Mike Truesdell’s three stages of learning: Analysis, Synthesis, Application.

Analysis

Listen back to the recording, making a written summary. This summary should be detailed enough to give you plenty of homework, align with your practicing themes, and also be capable of serving as reference matter in the future.

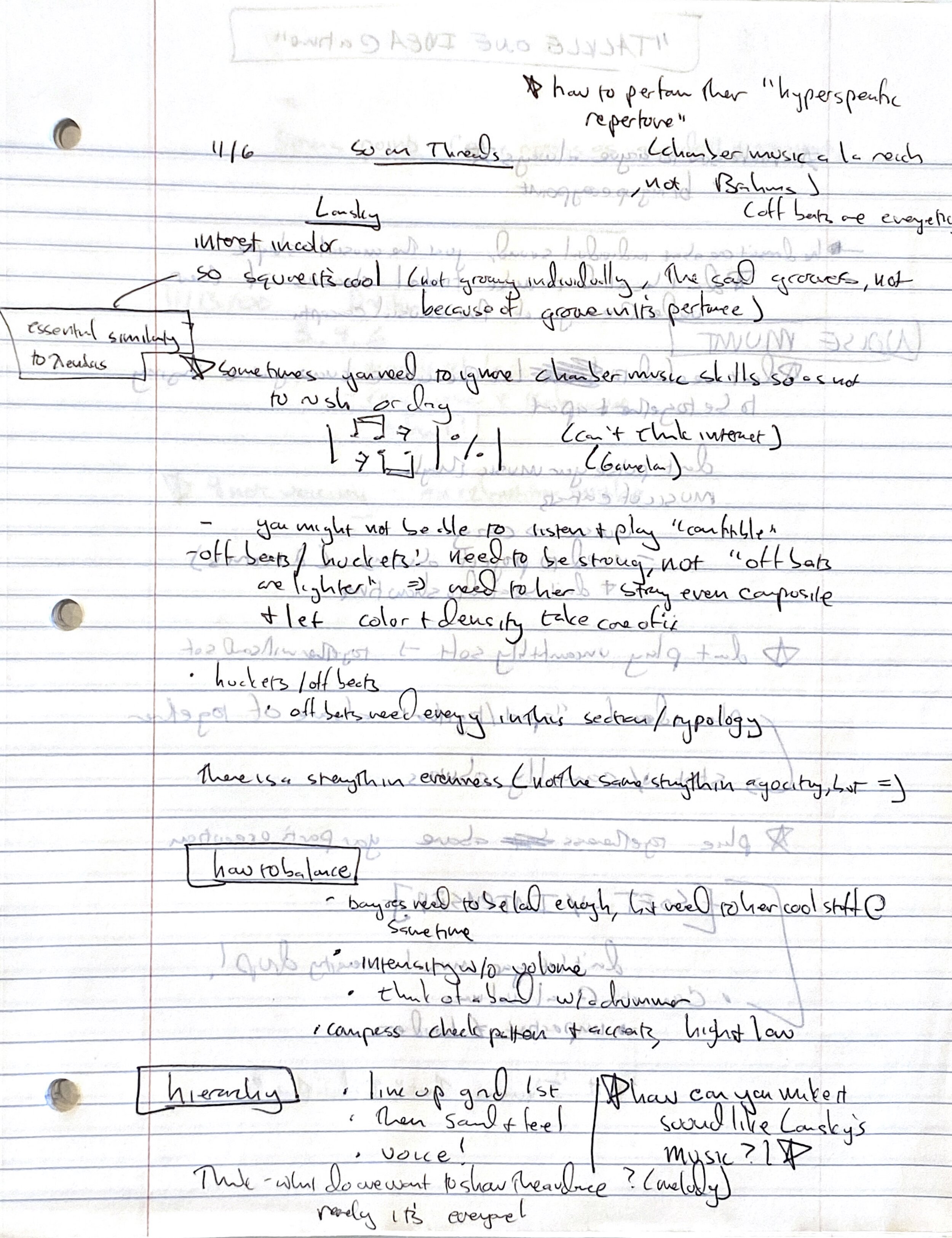

Here’s a summary from a lesson I took as a freshman at Peabody on Minoru Miki’s Time for Marimba, and on a coaching of Paul Lansky’s Threads. In both cases, In both cases, I tried to both summarize what happened in the lesson and provide some higher level organization of the more free-flowing events. Almost 20 years later, I have almost no problem remembering this content, although I still can’t read my own handwriting.

Then:

Assess your ability to change in the moment: were you doing what the teacher asked? Many times we think we’re making a concrete change, but our emotional biases blind us. Hearing the recording may explain why your teacher consistently asks for the same changes over and over and over.

Synthesis

Make a list of your key takeaways from the encounter. These ideas should focus your future practicing. Similarly, make sure to mark your music in accordance with the content of the lesson. Stickings, character markings, anything that you didn’t have time to mark in the lesson should make their way to your music. I recommend this step even if you think you’ll remember everything. On the one hand, multi-modal learning is essential for durable knowledge. On the other hand, studies show that our memory fades much more quickly than our perception of our memory. In other words, write it down!

Application

Create goals around your key takeaways, trying to make note of everything your teacher said. Great students don’t need assignments from teachers. One lesson should be enough content for weeks of work. My key takeaways from Jason Haaheim’s visit to KU “Great students bring problems to diagnose, not mysteries to solve.“ Your lesson recording should help you to try everything you can to make own your learning.

Practice Sessions: Ingestion

Goals: Get closer to your mental representation while prototyping methods of developing mental representation

How-To:

Pick a spot to work on, starting with smaller spans. Record yourself. Listen three to four times and make smart notes. I listen first for musicianship, and other big picture ideas, then for timing, then for intonation or tone quality, and finally for accuracy. Broadly speaking, I proceed along 2 paths from this point.

Option A

If you have a clear idea of what this passage should sound like, check your recording against your mental representation. Give yourself specific, detailed notes. “It sounds bad” is both poor grammar and poor analysis. “Eb in measure 5 is sharp,” or “consistently missing jumps between a 2nd and an octave in measure 2” is better, but still not great grammatically.

Then, make a smart, quick, repair, tackling one issue, using every practice technique you can think of.

Option B

What if you don’t know what’s wrong? You hit all the right notes, but something sounds off. If you don’t have one for this passage, but know something is not quite right, proceed with Option B, which is influenced by Design Thinking:

Brainstorm potential issues. Prototype a variety of changes, interpretations, or other variants. Try these quickly, and assess the effects. Perhaps inventing some exercises around the musical material can help focus your ears and hands? Then, proceed, circling back to option A.

Practice Sessions: Incubation

Goals: Refine your interpretation, combat stage fright by practicing performing.

How-To:

Choose a medium-sized chunk of music. Record yourself, and listen back, making specific comments on trouble issues. Categorize these problems: are these randomized occurrences or consistent? Small things (missed notes, bad transition), or systemic—a lack of dynamic contrast or tendency to compress fast passages? Make notes on the limits of your dynamics, tempi, character. Are they too narrow, too wide? Is your timing perfect?

Make a change, using the techniques outlined above. Tackle consistent issues first, then think about the larger issues.

I like to record in the medium scale because it helps me tackle performance anxiety. When we practice, our goal is to think critically about our own playing, diagnosing issues and planning our next steps. When we practice, that immediate feedback is a recipe for disaster. We can hone our performative skills by putting ourselves into “performance” mode, knowing we have our recording to help my critical thinking later. Over time, one can quickly enter this reflexive performance mode more readily. On this point, using a medium sized chunk is essential. Too often we practice our performance skills by making full runs of pieces. This is akin to jumping from a warmup to a marathon, with no smaller races in between. Not a great idea.

Performance Review

Goals:

Compare your memory of a performance to how it actually sounded.

Learn how to account for acoustics: timing, timbre, instrument choice

Refine the effectiveness of your portrayal

How-To:

Listen back to a concert performance, comparing your memories of the event to the recording. Does it sound the way you imagined? If not, what is different? Orchestral players will frequently use their colleagues or recordings to help hone their sound in different acoustics, calibrating their sense of their sound up close with the reality from hundreds of feet away. In chamber music, I find listening to a performance at a later date can help me calibrate my interpretations: did that moment land the way I wanted it to, or was my inflection too small for the space?

Some other recording situations worth mentioning:

Recording as Object

Goals:

Practice making a recording

Hone the skills of being a studio musician

Develop recording and editing skills

In recording studios, small scale inflections are less important, and larger consistency is more important. We can’t hear tiny details that really speak in live performance, but we do hear errors in timing and consistency, especially with percussion instruments.

Recording sessions are tiring, and have unique energy flows: long periods of low activity pierced by bursts of high-concentration. Why not become accustomed to this pacing by making a recording of a piece you know fairly well?

Similarly, making a demo recording can help you develop the skills of tracking and editing a piece. If you’ve been using recording in your practice, you’ve built up some technique within your DAW. By building upon the technological foundation you’ve developed in recording your practice sessions over a long period of time, you can put your new skills to work!

What to Do With the Recordings?

When Jason Haaheim visited KU, he shared his computer desktop with the percussion studio for a Powerpoint presentation. As his curser careened across his desktop to click “start slide show” (BTW, there’s a keyboard shortcut for this!), we messy, disorganized onlookers glimpsed the Jedi Archives: a perfectly organized database of excerpt recordings. I was in awe. Wouldn’t it be great to have everything I had ever played in one place?

This was ALMOST the moment!

My conclusion is: not really.

Although I do have a record (recorded or written) of almost every lesson I have ever taken, I treat my practice room recordings like post-it’s: a temporary memory aid whose value diminishes as its number increases. A desk full of Post-it’s is worse than no Post-it’s at all.

Why?

Similarly, I believe that I want to create what David Epstein calls ”wicked” learning environments (see last week’s post) when I practice, testing myself to remember what I was doing and how at precisely the moment that recall is challenging. Thus, my recordings often sound terrible.

The larger reason that my practice recordings are not valuable to me as documents, though, has to do with my larger goal in practicing. And they are not important to me as documents, since I believe in preparing to play something in infinite different ways, not honing in on one interpretation

I’d love to hear how you use recording in your practice routine. In the meantime, happy analyzing!