Welcome!

I am a percussionist, music-lover, chamber musician, teacher, curator, writer, and life-long learner.

I’ve moved most frequent updates to my two newsletters:

Older news below:

NEWS

Lost and Found

ALBUM ALERT

It’s such an honor and a privilege to be part of an album, especially when the work is collaborative. Here’s a new one:

I am so delighted to share a new CD release: Lost and Found, a collection of percussion works by longtime collaborator and dear friend Robert Honstein. This record features two recordings with which I’m involved: Down Down Baby, for two musicians playing one cello, recorded with Hannah Collins, and Lost and Found, a large scale work for prepared marimba.

I’ve been working with Robert since 2012, and I’m excited that these recordings capture his music’s virtuosity, whimsy, and expressivity.

This disc was truly a team effort: produced by Doug Perkins, recorded at Oktaven Audio and SHIRK Studios, mastered by Ryan Streber, and with stunning videos by Four/Ten Media, impeccably nostalgic cover art by Laura Grey, and an all-time great, liner note from Doyle Ambrust.

Alongside the immersive and powerful audio, we released a video of the titular Lost and Found, filmed in a swimming pool (empty) by Four/Ten Media.

Lost and Found emerged from experiments with marimba sounds in preparation for a cello/percussion duo which eventually became Down Down Baby. After years of workshopping, yards of foam, and multiple roto-toms sacrificed to the cause, we organized 33 of my amazing colleagues into a consortium and took the plunge (into an empty pool).

Real People, Alive on Stage

Robert’s Down Down Baby is an exemplar of New Morse Code’s philosophy of long-term collaboration. Leveraging musical friendships, we work to develop music which represents Hannah and Mike as musicians, not simply cello and percussion. Sometimes composers (in this case Caroline Shaw) even put our names in the the score.

In Down Down Baby, we sit opposite a single cello, neither string players nor percussionists, and explore with a childish glee. At the same time, DDB was developed over years of worshipping, trading ideas, and revisions, empowering our advocacy while embedding our own musical personalities into the music.

After years of practice on Simon, Hannah’s “you can touch this cello” instrument, a took to the parks of Philadelphia to play follow the leader:

Learn with Mike

Fascinated with drawing connections between all the learning we do in our lives? Interested in integrating these practices into your musical learning in a way that makes your process more effective, efficient, and powerful? Me too! Through November and December, I hope you can join me for three sessions about learning. I'll be going through my process live, and looking forward to learning from those in attendance. Hope to see you at one or all of the meetings!

Chef Wang is my favorite music teacher

I have a new favorite music teacher, and he’s a chef.

Wang Gang (王刚) was born in Fushan County, Zigong, Sichuan, and since 2017 has been uploading videos to Weibo (and later YouTube) highlighting the range of Sichuanese cooking to an increasingly broad audience. I’ve been a fan for a while, but he’s been increasingly on my mind as I think more about learning.

Watch a few of Wang’s videos (like this fish-fragrant eggplant tutorial) and you’ll notice a pattern (if you don't speak Chinese, be sure to use YouTube’s caption button):

Wang introduces the dish

Wang processes the ingredients, highlighting the cooking process and in the process dazzling us with his knife-work and wok skills.

Wang provides a summary of the dish, offering a few tips for cooks at home.

Or take this spin through a pork rib braise, where Wang walks us through the how and why of cleaning the pork, adjusting the recipe for a home stove, even providing an executive summary, all in under 3 minutes.

It’s almost impossible to overstate how good of a chef he is. Wang’s technique is almost hypnotic, occupying the same part of my brain as a perfectly executed snare drum roll. I could watch his cleaver destroy garlic and ginger, neatly organized cucumbers, or gently fillet a fish for hours.

Wang shines in technique-heavy dishes, where his skill and effortless mastery are on display.

Wang is straightforward, clear, focused, self-effacing, and fast. His narration is calm, and he speaks with the efficiency of Strunk and White. Even the austerity of his surroundings and simplicity of his tools are on message. He doesn’t need a special device for it anything, and cooks almost every video on his channel with a single cleaver and a single wok.

At times, Wang shares technical videos, such as this not-so-subtle level-up on your home knife-sharpening:

Most of my students will tell you that my analogies are almost all cooking, so it’s no surprise I spend some of my free time watching cooking videos. But what was it about Chef Wang that had me so captivated? Yes, I was primed for appreciating his work, having grown up with Jacques Pepin, Julia Child, the Frugal Gourmet and their PBS cohorts demonstrating in real time why cooking wasn’t so hard. But Chef Wang touched upon something else. Was it the pangs of hunger at the food his pitch perfect technique was creating?

It was what I was learning about teaching, and by extension, learning.

What can we learn from Wang Gang and his gestalt?

How to cook

We can learn a lot about cooking! With Wang’s clean and consistent technique, disciplined attention to fundamentals, and broad repertoire, we do learn a lot about how to effectively cook and appreciate the dishes he espouses. Through Wang, the depth, range, and brilliance of Sichuan cooking comes to life.

How to Learn

Perhaps more importantly for those not interested in braising a carp or cleaning pork liver, Wang teaches about how to teach. Although some of Wang’s videos show him actively teaching, most of his solo ventures demonstrate a virtuosically economic pedagogy. He picks significant dishes about which he has something to say, articulates a frame for his work, highlights important techniques and concepts through modeling, and reinforces his work with a clear summary which frames larger topics. His clarity belies a deep fundamental knowledge, skill, and experience. Wouldn’t we all love to be such a lecturer?

The power of analogy

From Wang we can also learn about how we can improve our musical skill. In fact, I would argue that for we musicians, studying how we might learn other skills provides a terrific framework for how we might refine our own. When we think in analogies we pay attention to structural similarities. To meaningful compare something to something else we have to know what those things are at their deepest levels. That’s powerful.

There’s something about the interplay of fundamental technique and individual artistry, history and innovation in cooking that proves a strong analog to making music. These thoughts are a little more likely to enter our mind via a non-musical analogy.

Chef Wang’s Neighborhood

The most important thing I learned from Wang is exemplified by the transformation in his channel after he moved back to his hometown and began making videos there. While his production value improves, he gains an audience: his stoic, practical and honest aunt and uncle.

Cooking under his Uncle’s watchful eye, Wang provides helpful clarifications to his dishes, and feeding his family seems to inspire a richer, more effusive cooking. These videos also begin to add meaningful feedback. How does his food impact others around him? His circle grows to include students, the presence of whom moves Wang into a more overt teacher, and he easily moves from modeling to critique, even of his student’s eating speed.

Sometimes he goes full Mr Rogers, visiting factories, restaurants, farms, and other culinary locations, even taking over a dumpling shop. At other times, he learns how to butcher a pig from his Uncle.

Why have I really been so interested in Chef Wang? It’s because his work perfectly highlights my beliefs around learning, namely the through-line between technique and community.

Wang has leveraged a rigid classical training to engage with people he cares about in a meaningful way. Most of his recent videos end with the satisfaction of a shared meal, or begin with a shared experience that requires cooking. In this way, Wang highlights the vitality of community in our artistic pursuits: the framework of his technique allows him to effectively convey his ideas, his breadth of experience allows him to tailor his content to his audience, and, most importantly, he uses all of his skills to enrich people’s lives.

Thus, Wang slicing and dicing on the way to feeding his aunt and uncle are neat analogues to how we hope to nourish our communities with art. And, his deep dives into soy sauce and why you should always have water running at your wok station highlight how every expert goes deep into the weeds, and only true masters can emerge to the zone of abstraction and clarity. He makes clear the linkage between mastery and community, between emulation and transformation. For him, cooking is the emulsifier, although it might be any activity.

If you haven't noticed, I’ve been thinking a lot about how multifaceted learning strategies can help us be stronger community builders. For those of us struggling to connect the technical studies we do with our public facing work, a chef is a terrific example to follow. All it takes is a lot of pork, and a few uncles.

Mike

Can reading a map make you a better musician?

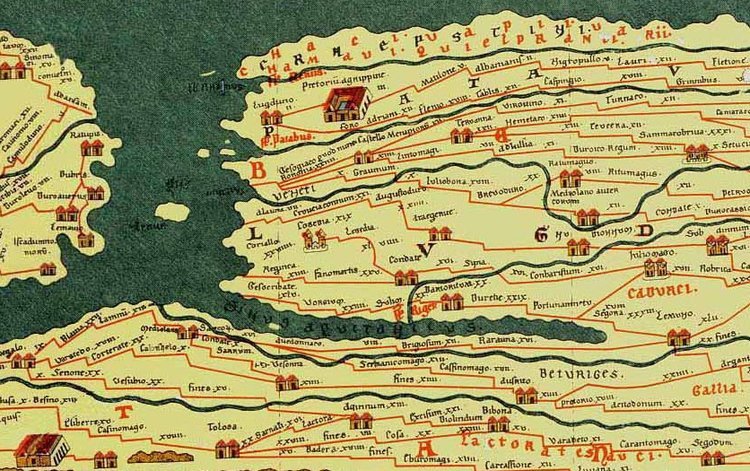

In the last few weeks, I have been deep in the weeds. With maps. It started with discovering the Atlas Catalá, (Catalan Atlas), a mappamundi from 1375 thought to be created by the Majorcan cartographic school, a collection of predominantly Jewish cartographers and mapmakers working in Mallorca before Spain’s expulsion of the Jews (1492). It highlights known locales and their religious/political allegiances. The text is oriented towards the edge of the page since readers would have walked around a table to read

The mappamundi piqued my enduring interest in maps. How about this one, this map, a copy of which has been hanging in my parent’s house as long as I can remember:

A French version of the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela. The cities are not hierarchical with regard to size, but with regard to their religious and geographic significance: who visited where, what is on the way to where. In fact, the map lists some “fan favorite” routes on the right hand side. It has all the trappings: crests of the Spanish Monarch and the House of Bourbon, the cross of St. James, and a nice call to arms (“Dios, Ayuda, y Santiago”). It even has decorative boats taking on the pilgrimage route by sea, just in case those dotted lines over the ocean weren’t clear. In typical French fashion, most of Spain has been replaced with images of St. James as a pilgrim, adorned with his go-to scallop shells.

While the above is certainly a modern invention, it’s based upon the tropes of 17th century map making. I love that this map is a one-stop shop, rolling cultural history, politics, and travel planning into one convenient package. More importantly, this could be a map one reads on the way somewhere, much like my beloved Michelin maps, which I love to unfurl imagine the terrific places one could go.

Happy place: map store

Speaking of routes, what about the Romans, who by many accounts did not use geographically signifying maps?

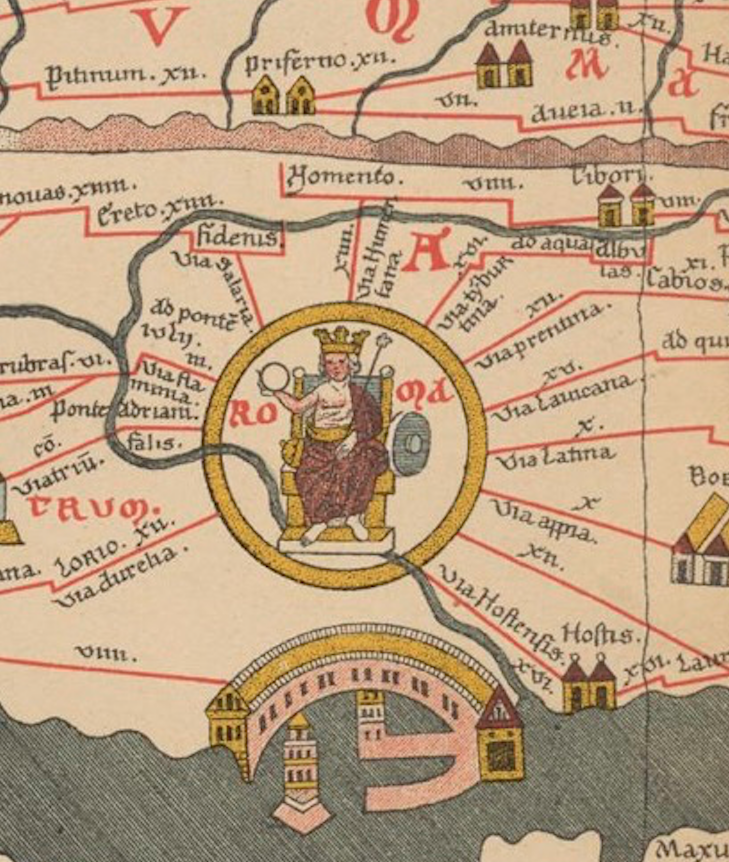

Instead, they navigated with itineraries (itineraria) which directed travelers from milestone to milestone along the Roman cursus publicus (road network). These are scenes from the Tabula Peutingeriana (Roman itinerarium), a 13th-century of an original from around 12BCE and later engraved in marble in the Roman Campus Agrippae.

Check out the full size Tabula here 🤯

These are schematic maps, deemphasizing geographic features in favor of connections. Here milestones on the cursus are depicted in parallel lines (north is left). Since most travelers would not have had a map, the most salient information would be “what is the next city I’ll pass” and “how far away is it.”

What do maps have to do with contemporary music, the supposed subject of this newsletter?

Reading a map is an interpretation:

All maps have a bias, from the choice of projection, to the selection of a scale (unless you are Borges), to the curatorial decision of what to include (my beloved Michelin maps sure do include a lot of roads), these biases range from passive, to active, like this amazing rendering of the Washington DC Metro by Andrew Bossi:

Generally speaking maps say more about the people making them than about the places that are being mapped. Who is the map for? A king isolated in their castle, or a travel writer exploring the world? Who is it not for? What is left out, kept in?

More importantly, (most) maps need somebody to read and interpret their biases. That reader brings their own contemporaneous ideas to the reading. Sounds an awful lot like a point famed musicologist Richard Taruskin makes in Text and Act, where he argues that performance practice of 17th and 18th century works says more about the society performing them than the “original intent” of the composer. In fact, arguing that “original intent” is an important parameter is a uniquely modern idea. I think all of us who have seen a Shakespeare play set in a post apocalyptic future world or a Verdi opera set in a 1950s office can make sense of this argument.

2. Maps and prescribe and describe

My mind keeps catching on the juxtaposition between prescription vs description so elegantly expressed in maps, particularly the Roman Tabula above. That maps is prescriptive—it tells the reader what to do rather than describing the world.

In his 1958 article “Prescriptive and Descriptive Music-Writing,” musicologist/folk musician/Bob Dylan listener Charles Seeger argues that musical notation can be either prescriptive or descriptive. In prescriptive notation, the emphasis is on structures (typically structures of pitch and meter). The notation does “not tell us much as much about how music sounds as how to make it sounds.” Descriptive notation endeavors to display the work “as it is,” through graphics of sound waves or other means.

I have been thinking this week about musical scores, and how most musical notation is prescriptive or symbolic. Sometimes, a score might include so many prescriptions that the implication becomes that what is essentially prescriptive is in fact a description of the music, requiring no other input from a performer and no other historical or intuitive insight. Our scores are most effectively is abetted by oral performance practice traditions: performers who have worked closely with performers, composers sharing (passively or actively) their notions of a range of acceptable interpretations.

So what are we as interpreters to do? We have a very clear distinction between text and the performance of that text. (Whether that should be the case is a subject for another newsletter) Stated a more proactive way, art needs people to grapple with it, and need communities to make sense of the people making sense of the texts.

3. Maps are mental representations

With the arrival of a new semester, I, like my professor brethren, have a renewed vigor around what we teach and how. In particular, I’m more interested than ever and how we learn, particularly how we learn music.

Central to our learning in music is the notion of a mental representation. Popularized by Anders Ericsson in his book Peak, a mental representation is “a mental structure that corresponds to an object, an idea, a collection of information, or anything else, concrete or abstract, that the brain is thinking about.” More to the point, they are worldviews. These conceptions of the world can broadly be construed as mental representations. Although motor learning experts might rolled her eyes at my definition, I believe a mental representation is a multi sensory sense or perspective developed through exposure and practice about why something is the way it is, and more importantly, what is wrong when something is wrong.

Now, is a map a mental representation? Your answer might immediately be no. Most maps are created so that people don’t have to remember the location of information, or a culturally significant location. But, they are. A map represents an idealized (to someone) version of a place. A lot is left out, and those omissions are in many cases very purposeful distinctions. Is this not a sense of how things should be, a worldview? A super heuristic?

This year, I’m interested in how teaching can be about helping people bring color, nuance, and perspective to their mental representations. If one’s students have a strong sense of how things should be, they can effectively teach themselves. But, it is not enough to have a sense of what is right, how a piece of music should sound. One must have the critical perspective to indicate and understand why your perspective is but one of many. In fact, aren’t our most epiphanic experiences the ones through which a new piece of information conflicts or rubs against our current conception of the world?

As performers and teachers of music, our goal is to facilitate not only a rich sense of the way things should be, but a critical lens on why you might believe what you believe about what you believe. So, we tend to learn by comparing what we don’t know something we do know. If you know maps, get ready to learn about music.

Now, is a map a mental representation? Your answer might immediately be no. Most maps are created so that people don’t have to remember the location of information, or a culturally significant location. But, they are. A map represents an idealized (to someone) version of a place. A lot is left out, and those omissions are in many cases very purposeful distinctions. Is this not a sense of how things should be, a worldview? A super heuristic?

This year, I’m interested in how teaching can be about helping people bring color, nuance, and perspective to their mental representations. If my students have a strong sense of how things should be, they can effectively teach themselves.

But, it is not enough to have a sense of what is right, how a piece of music should sound. We must have the critical perspective to indicate and understand why our perspective is but one of many. In fact, aren’t our most epiphanic experiences the ones through which a new piece of information conflicts or rubs against our current conception of the world? As performers and teachers of music, our goal is to facilitate not only a rich sense of the way things should be, but a critical lens on we believe what you believe about what you believe. we tend to learn by comparing what we don’t know to something we do know. If you know maps, get ready to learn about music.

Ok, back to *Transit Maps of the World*.

Mike