Welcome!

I am a percussionist, music-lover, chamber musician, teacher, curator, writer, and life-long learner.

I’ve moved most frequent updates to my two newsletters:

Older news below:

NEWS

Thinking more on Pre-Practice Rituals

If you’ve been following my recent posts, you might have noticed that I’ve been working through my thoughts on how we might learn music with an eye towards innovative interpretations. Thus far I’ve laid out some of my ideas on why historical study can be a good idea.

Let’s catch up:

You might say “finally! We can finally practice. Cancel my plans and break out the Pomodori!”

NOT SO FAST.

Pre-practice work prepares you for deep work while practicing while priming you. Your study, analysis, score preparation; they all help you ritualize your work, make grand gestures, and set you up to execute like a business.

By now you might be feeling comfortable situating the piece you are learning within a broader cultural context. You might also feel confident talking about the music of the composer you’re studying in a nuanced and detailed fashion. You are able to articulate general characteristics of the composer’s output, point to specific works as exemplars. You stand at the ready in case a prestigious university calls and asks if you’d teach a seminar on the composer’s work (a GRADUATE seminar, no less—perhaps in a wood-paneled room with a dark mahogany table).

You’ll develop your own metric for how much is enough with regard to broad context—it should change throughout your career, of course—but I measure my readiness to move to a piece-specific study on a sliding scale. Teaching a graduate seminar on the piece is at one end, and making a good conversational point at a cocktail party at the other.

We have more work to do.

When learning a new work, your goals when practicing should be (in any order)

Develop the musculature and physical technique necessary to undertake the demands of the work at hand

Learn the piece, taking in all notes, rhythms, dynamics, expressive markings, formal concerns, characters, tempi; anything in the text of the piece

I had a teacher who would shout “know means know!”

Develop an range of interpretations you find to be not simply valid, but revolutionary and communicative

In the process, develop a set of physical practices that can help determine that you produce your desired interpretation with accuracy and precision and without performance anxiety

You can see how knowing something about the piece before you set stick to drum or bow to string might help speed this process up. Or, having your music prepared and marked to facilitate efficient practice sessions. Or having listened to some recordings and developed some hypotheses about how you might approach the work. Pre-practice rituals are the superpower of the mature classical musician.

If you’re new to pre-practice rituals, don’t skip them. Rituals are foundational in getting yourself into the right mindset to learn, to focus, to drown out outside distractions. While everyone has their own practices before they practice, these are my steps.

Pre-practice rituals are more valuable to our learning than you think.

They set you up for deep and meaningful work and engender brilliant and dynamic interpretations. Don’t skip them!

My steps:

Listen and Analyze

Prepare the part

Plan your learning

Listen and Analyze

Listen to the piece with and without the music. Fall in love!

Hear intuitively and buttress your intuition by asking and answering questions about the work. Use words to describe what you’re hearing

Visualize: what will it feel like to perform this piece?

The goal of our analysis is to buttress our intuition, to enable our ability to connect with audiences, to engender the transformative power of musical performance. Nothing less. These steps will keep you fully committed to your oath to performance and connection, not writing a journal article (yet!)

Get your music ready

Print the music on high quality paper (nerd out!)

Figure out your page turns/tape

Mark Your Part:

Use colors

Give yourself performance instructions

Caring about these details develops your attention to detail and is a proxy for your commitment to an impactful performance

Plan your learning

Find your depth philosophy and ritualize

Make a schedule

Set goals

Create a mental representation before you practice

Creating a ritual and rhythm around your work gives you the freedom to be creative. Likewise, leveraging your musical analysis to give you an interpretation BEFORE you practice is key!

So far I’ve written thousands of words on this topic. Looking forward to sharing them in a more organized fashion!

Finding your Depth Philosophy and Getting to Work

I liked to think of myself as an adroit concentrator, but it wasn't until I brought rigor to how I focus that I started to be able to generate my best work reliably and regularly and with minimal friction.

As the semester here in Arizona becomes increasingly hectic, I have been revisiting Cal Newport's Deep Work to remind myself of some best practices for focus and concentration.

Deep Work is focused uninterrupted, and productive work on any task. It mobilizes as much of your mental energy as possible, reducing distractions to a murmur and enabling your progress to compound. Broadly similar to Deliberate Practice—the scientific method applied to skill development—and flow, that thrillingly elusive balance between challenge and skill, Newport posits Deep Work as a way to help tune out the distractions of contemporary life while training your brain to focus more effectively and powerfully.

For those of us struggling to find depth in our work amidst the noise, I want to share some of the lessons I took from Newport's work, particularly ideas about how to find one's Depth Philosophy and some practices for reducing the friction around getting to work.

What's Your Depth Philosophy?

Your goal should be to find strategies, routines and rituals that get you into a deep, undisturbed focus with less willpower. Central to that quest is understanding your Depth Philosophy, how Deep Work is integrated into your professional life. Four models include:

Monastic

St. Jerome spent a LOT of time in Deep Work

Monastic workers devote long spans of time to a single task, eschewing almost everything else for months. They always have a vacation email response. If you need consecutive, uninterrupted chunks of time (say, if your success comes from doing one thing really well, or if you're in a field where you have a well-defined and highly valuable professional goal), you need to find a way to create this time for months on end. Any separation or fragmentation will result in precipitous drops of productivity.

Bi-Modal

Bi-Modal workers dedicate some clearly defined stretches of time to deep pursuits and leave the rest of their schedules open to "everything else." During Deep Work sessions, a bi-modal worker will behave monastically—maybe without the beer brewing, but still distant and focused. I think of this model as the "artist residency" philosophy. Musicians rehearsing for a project or artists at residencies will set aside weeks to work on a single creative project with verve and intensity. When they emerge, they find balance in their lives another way. I see Bi-Modal work every summer at Avaloch Farm Music Institute, where chamber ensembles and composer/performer collaborations come to remote New Hampshire to work on creative projects for weeks on end. Here’s a set of posts I wrote about this experience and the powerful synergy present in residencies.

Rhythmic

Rhythmic workers realize that disappearing for weeks at a time is not great for most jobs. They rigorously schedule blocks of time in which to work, keeping to them as much as possible. A rhythm of productivity is powerful and compounding.

In music we see this all the time—composers who write music at the same time every day, performers who practice without fail each day, and ensembles who rehearse the most basic of material regularly.

Journalistic

Journalistic workers fit Deep Work wherever they can into their schedule. They can shift into work mode on a moment's notice, a particularly useful skill to have if you work in a deadline-driven profession. Working Journalistically is challenging. Newport notes that "the ability to rapidly switch your mind from shallow to deep mode doesn’t come naturally." He also argues that quick deeps to high productivity requires high confidence, a "conviction.…typically built on a foundation of existing professional accomplishment. “

Most musicians are somewhere between Rhythmic and Journalistic workers on their own, and adopt a bi-modal approach to collaborative projects. They develop their craft with regularly but respond to deadlines with spurts of their best and most focused work. They're flailers and toilers and intermittent bingers.

What next?

Knowing your ideal “Depth Philosophy” around work can help you more meaningfully integrate Deep Work into your practice. But, how can we keep the world from invading while we're working? How can we get better at focusing? Newport gives from great ideas that have been game-changers in my own work and teaching.

Rituals: Not Just for Cults and Pierre Boulez

First, work to ritualize your work. Newport argues that "great artists work like accountants," leveraging strict habits before and during work to avoiding having to wait for inspiration to strike. Your rituals could be when you work, or for how long. They could be where you work—commuting to an office, or shutting the door to a room. They could a signal, like getting dressed a certain way, drinking a coffee, or (for me) getting out my metronome and some chocolate. Your rituals also encompass your best practices while you work, a set of habits that work to compound your effort. Supporting your efforts to go deep with some more rigid structures helps get your mind comfortable enough to generate new ideas. This might be why "highly effective people" have habits.

On a side note, the habits of great artists are alternately fascinating and boring. I recommend Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: How Artists Work for a window into the rigid work and flexible socialization of famously productive.

Getting dressed for work can be a powerful ritual

Those who know me know that I have a process for almost any productivity challenge. My processes are my rituals, methods I’ve developed to get my mind and body set to learn something new. Likewise, if writing or researching, I am obsessive about my note-taking and outlining, which helps my recall and keeps me focused.

Make Grand Gestures

Even though systematized work is essential, Newport argues that sometimes a big project necessitates a radical change in work environment to engender serious commitment. He notes that “to put yourself in an exotic location to focus on a writing project, or to take a week off from work just to think, or to lock yourself in a hotel room until you complete an important invention: These gestures push your deep goal to a level of mental priority that helps unlock the needed mental resources”

A Grand Gesture is in the eye of the beholder: you do not have to mirror JK Rowling and rent a hotel room until you finish your book. You could set aside an entire weekend to finish a task, or lock yourself in a room until you finish that annual faculty report (I know the feeling), or withhold chocolate until you learn notes (oh cruel world). The key feature is to get something to be your main mental priority.

Don't Work Alone

Not even Tin Tin worked alone all the time.

Even though much deep work for musicians is solitary, properly leveraging collaboration is an essential tool to increase the quality of your work. Newport talks about ways of generating "serendipitous creativity" through a combination of isolation—deliberate practice—and chance encounters with others, opportunities to bounce ideas off another set of ears and receive meaningful feedback. Most musicians know this intuitively. Sometimes that walk to the water fountain is about more than just refilling your water bottle!

Execute Like a Business

First, focus your execution on the most significant goals. Simplicity in outlook—what I call the "themes" of my practice—focuses your energy. Identify a small number of ambitious outcomes to pursue with your time rather than a large number of small goals. Then, find a way to keep a score card of your work, a physical or digital artifact that displays your progress. The mission is to create a “cadence of accountability” in your work, be it regular team meetings, or a weekly review session to make a plan for the coming week. Jerry Seinfeld says “don't break the chain:” keep at your work each day to get in the habit of working in a focused manner. If you work more effectively in teams, look for ways of modeling that in your solo endeavors.

I'm more effective working in teams. While in school, I developed "acountabilibddies," friends to whom I would tell my more individualized goals. My friends would definitely know if I didn't finish learning that piece or writing that paper, so their awareness kept me on track.

Finally, Newport encourages us to both be lazy and embrace boredom. By injecting forced down time into your schedule, your brain has time to process your work and prepare for the next day. At the same time, during work sessions Newport encourages us to think about taking breaks from focus rather than taking breaks from distractions. Checking Twitter while writing an article doesn't destroy your focus muscles. Instead, Newport argues that 'he constant switching from low-stimuli/high-value activities to high-stimuli/low-value activities, at the slightest hint of boredom or cognitive challenge, that teaches your mind to never tolerate an absence of novelty.” No absence of novelty = no presence of amazing new ideas.

Training your brain to stay on task even when bored is challenging, but the reward is quick and easy access to your mind's unfettered creativity.

Drain the Shallows

I also appreciated Newport's concept of "draining the shallows," the systematic reduction of work that is not your deepest work. What's shallow work? Answering emails that someone else could easily write. Filling out paperwork. Newport argues that we should treat shallow work with suspicion because its damage to our ability to do deep work is often vastly overestimated. Not only does shallow work—everything from deciding on a new model of space heater to filling out annual faculty reports—eat up valuable time, but it also diminishes your ability to work deeply by training your brain to only tackle tiny tasks.

I (try to) use Newport's 3-part strategy to reduce shallow work:

Schedule the entire day. By setting aside blocks of work, you set the stage for insights. 5 hours of free time does not = 5 hours of work.

Quantify the depth of your activities. Ask yourself how long it would take to train someone to do the task at hand, and wonder (aloud if you need to) if the activity leverages your expertise and experience.

Make a shallow reach budget

Tin Tin keeping up with his shallow work (note, he’s not working alone!)

Overall, work to put yourself in a position to say no to projects that are shallow while reducing shallowness in existing projects. While nobody can step away from all tiny tasks indefinitely, we can ask ourselves how little time we're producing value and what activities we could step away from to increase that time. I've tried to start keeping a budget of how long I can set aside for shallow tasks each week, and I try to leave it at that no matter how itchy I feel.

For those who work with me, the influence of Newport's ideas is straightforward to see. His work has helped me blend notions of Deliberate Practice, flow, and time-management in a meaningful and parametric way. Hope it's valuable for you as well and looking forward to hearing from you about your own rituals and Depth Philosophies!

Recording in the Practice Room

Why Record Yourself?

As I’ve discussed in a previous post, learning is a combination of experience and reflection. Recording jumpstarts this process by allowing the experience to be observed from a number of perspectives without worrying about time, which allows for a more nuanced, critical reflection. More experience + more reflection = more learning!

Similarly, recording provides instantaneous, unbiased feedback about your playing. One of the central tenants of both Deliberate Practice and Design Thinking is that learning requires feedback. With recording, feedback is immediate, and unbound to our biases about our playing. When we learn, we struggle when presented with what David Epstein calls “wicked” learning environments: situations in which feedback is not immediate and in which previous experiences do not imply a future strategy. Because of its immediacy and objectivity , recording oneself in effect turns a ”wicked” learning environment into a ”kind” learning environment.

How? Recording aids in the development of mental representation around our playing, and is like having a teacher in the room with you. In Peak, Anders Ericsson explains that a mental representation is “a mental structure that corresponds to an object, an idea, a collection of information, or anything else, concrete or abstract, that the brain is thinking about.” Thus, “the main thing that sets experts apart from the rest of us is that their years of practice have changed the neural circuitry in their brains to produce highly specialized mental representations, which in turn make possible the incredible memory, pattern recognition, problem solving, and other sorts of advanced abilities needed to excel in their particular specialties.” When we record ourselves during practice, we supercharge that developmental process.

Recording also meshes nicely with the problem solving strategies espoused within Design Thinking, which prioritizes brainstorming many ideas and quickly testing them. Recording is perfect for these tandem processes of ideation and prototyping.

How I use recordings differently than some of my colleagues

My philosophy around recording myself differs from a “pure” application of Deliberate Practice. While Deliberate Practice has as its stated goal the refinement of a narrow band of outcomes (“this is the way”), buttressed by a guru and a clearly-defined learning modality, I prefer to use the tools of Deliberate Practice to achieve the skills of generalization, flexibility, and creativity. Deliberate Practice is both a technique and a philosophy. I prefer the technical elements, but want to avoid the implication that our end goal is perfection of a single performance practice.

My musical goal is to be able to play everything in myriad different manners, and so I use my recording to help develop maximal flexibility. Why is flexibility better than honing one way? In Range, David Epstein demonstrates that those with extreme domain specific knowledge and narrow bands of pattern recognition can’t adapt to new situations. And since you’re going to be working with lots of people who will ask you to change things ASAP to get $$, flexibility seems a valuable and pertinent skill.

What You Need

Good Quality Audio In and Out

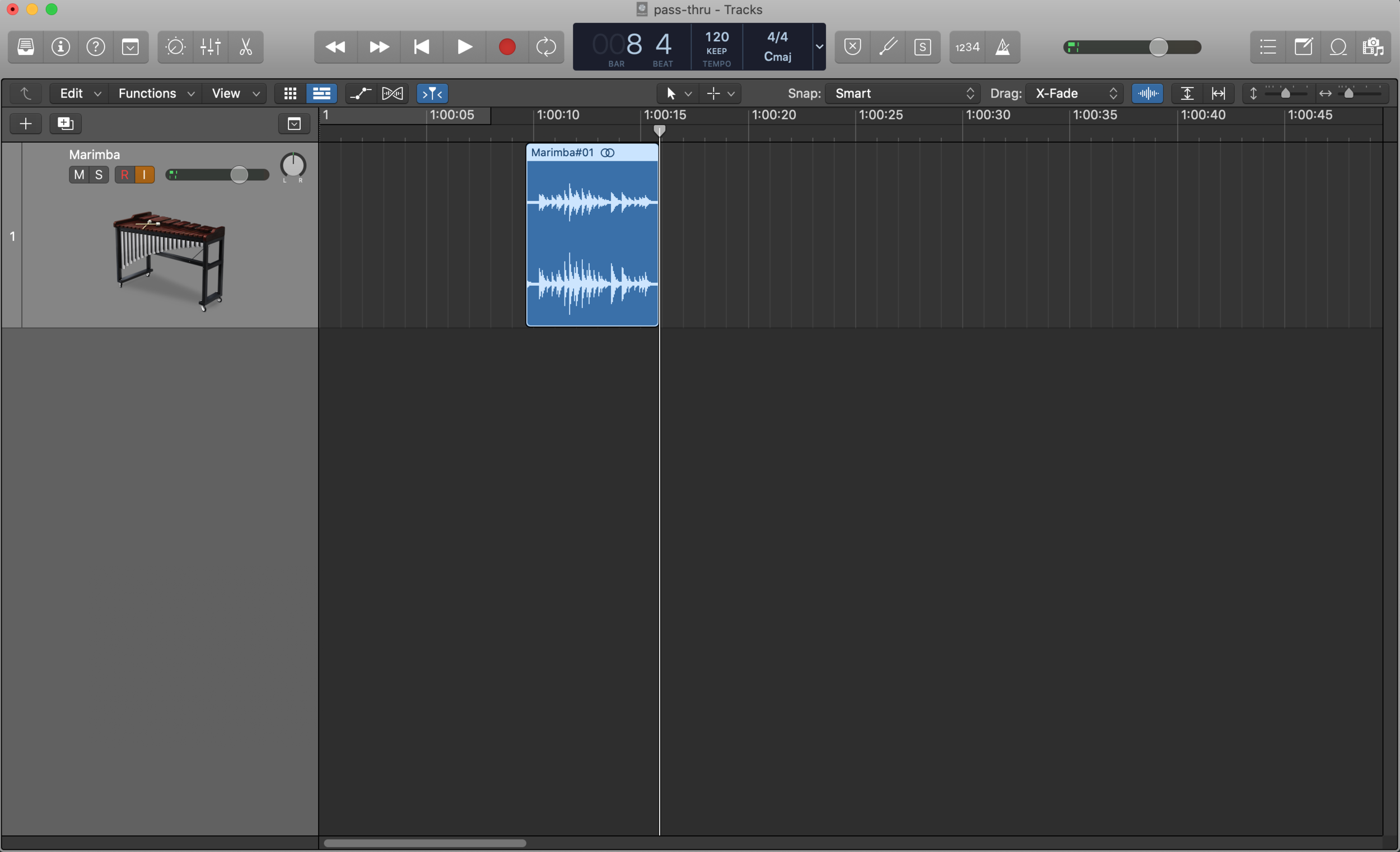

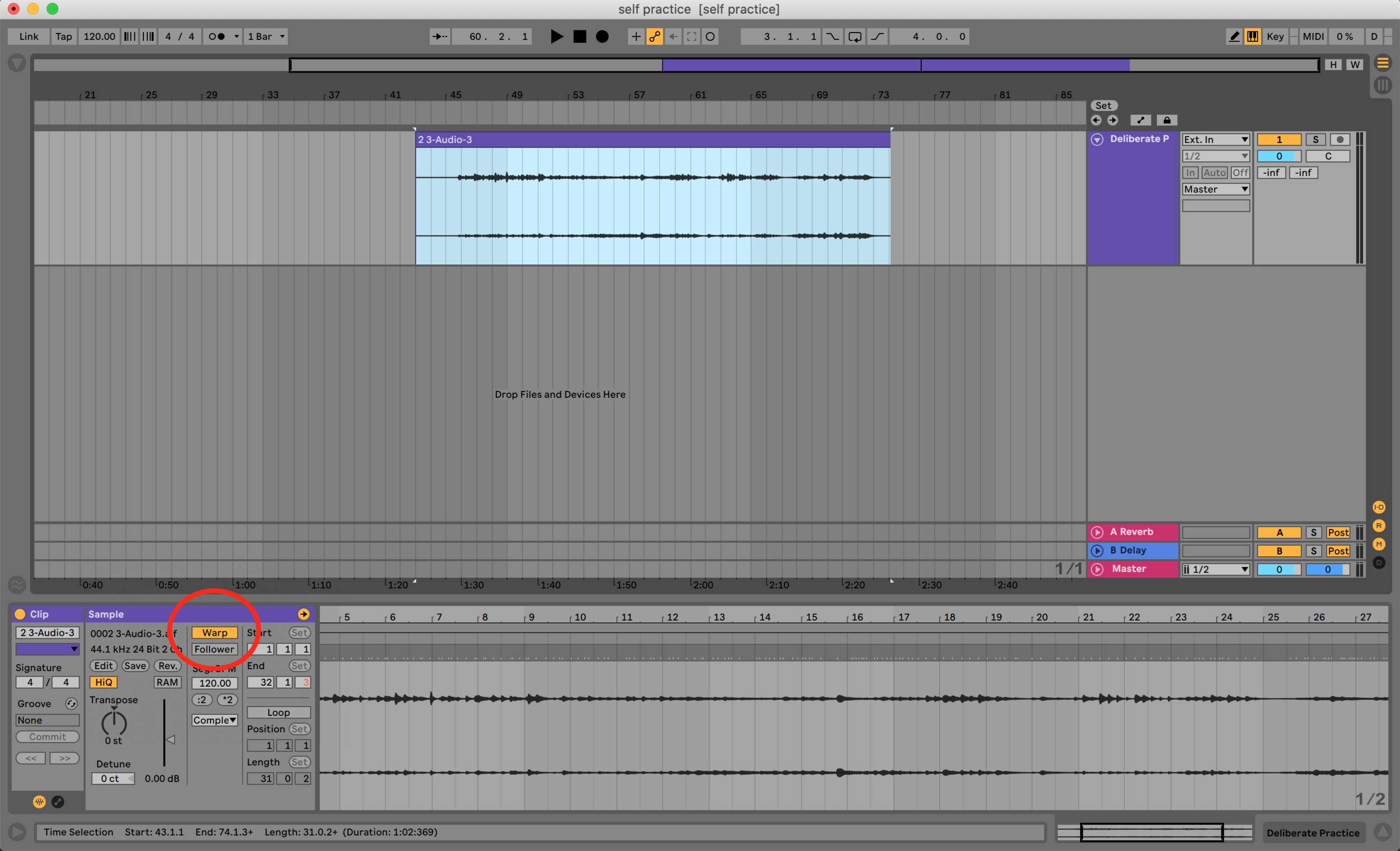

My setup is stereo mics with audio interface and either Logic or Live. I prefer recording into software rather than to a standalone recorder because I like being able to quickly edit audio, loop passages, and compare against previous recordings while using visual and software inspection of waveforms as a quick check of my precision and consistency. On the road, I typically use a Zoom H4 or H6 for quick and dirty recordings. USB microphones are terrific these days, and the plug and play element is very helpful. Make sure you allow plenty of cable length to get a good sound from your sofa—I mean marimba. Personal preference is salient in DAW choice, so try a few out and see what works for you. I use a combination of Live and Logic: Logic because I’m comfortable with the interface for recording and editing, and Live for the ease of changing the tempo of my recordings.

If the goal of our practice is to refine and develop our sound concept, we need good output as well as input. Either good headphones or good monitor speakers can help you make quality decisions about your sound.

Peabody’s list of recommended equipment is a good jumping off point if you’re just getting started.

The Ability to Slow the Recording Down

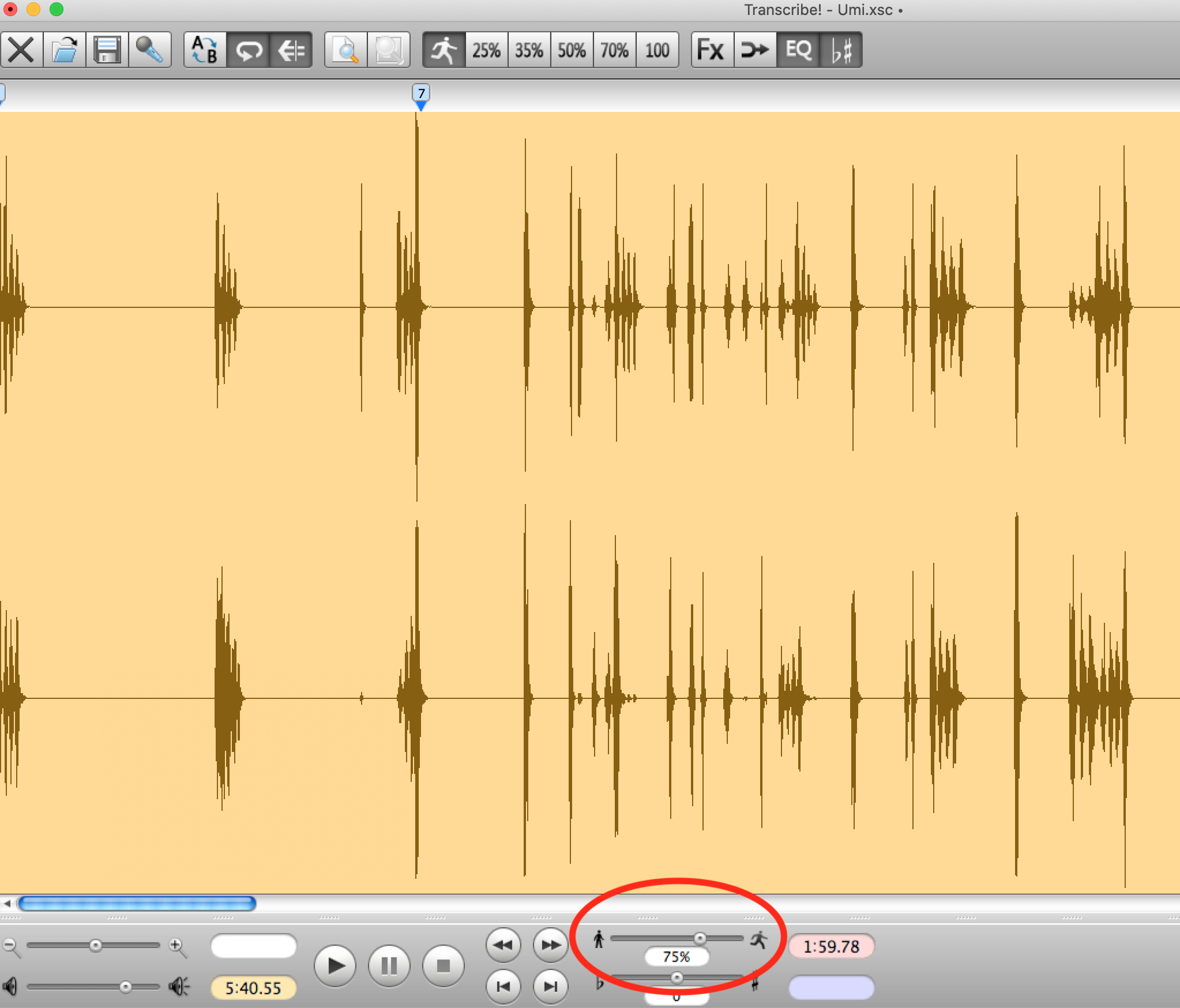

I like to slow down my recordings to more accurately assess issues. Although most DAWs can change tempo without impacting pitch, Ableton Live’s warping feature is perfect for real-time adjustments. Transcribe! works wonders as well, although importing sound files into the program can be just slow enough to discourage me from using it.

Notebook/Practice Journal

I use a notebook (well, a OneNote notebook, sorry Todd Meehan), to keep track of my notes, and to make assignments for myself. I tag assignments and then periodically review and summarize my goals so that I can always enter the practice room knowing what I need to accomplish.

Why no Video?

I typically record audio only in my practice sessions. Why? Video can lead to unnecessary bias. We have a tendency to listen with our eyes, saying that a passage sounds a certain way because it looks a certain way. It opens the door for dogma, and it’s a slippery slope towards the kind of narrow-banded thinking which cripples specialists. That kind of subjectivity is the opposite of what we’re trying to achieve when we record ourselves.

Finally, working with video is incrementally more challenging than working with audio. Video files are slightly more challenging to edit, and the larger file sizes are moderately more annoying to manage. ”Moderately more” is enough to discourage me from recording (I read Nudge, didn’t you?), so I keep things to audio unless I’m working with larger chunks.

Recording Situations

Lessons

Goals: documentation, reflection, synthesis, goal-setting

In a lesson, we pay close attention to our teacher’s words and actions. We throw ourselves into trying things in new, uncomfortable ways. Great teachers are masters at pacing, so after a terrific lesson we might not remember everything that happened. That’s where recording comes in. Students who record lessons improve exponentially.

How-To

After asking your teacher if you might record your lesson, record the lesson. Then, get to work. My philosophy on lesson recordings aligns closely with Mike Truesdell’s three stages of learning: Analysis, Synthesis, Application.

Analysis

Listen back to the recording, making a written summary. This summary should be detailed enough to give you plenty of homework, align with your practicing themes, and also be capable of serving as reference matter in the future.

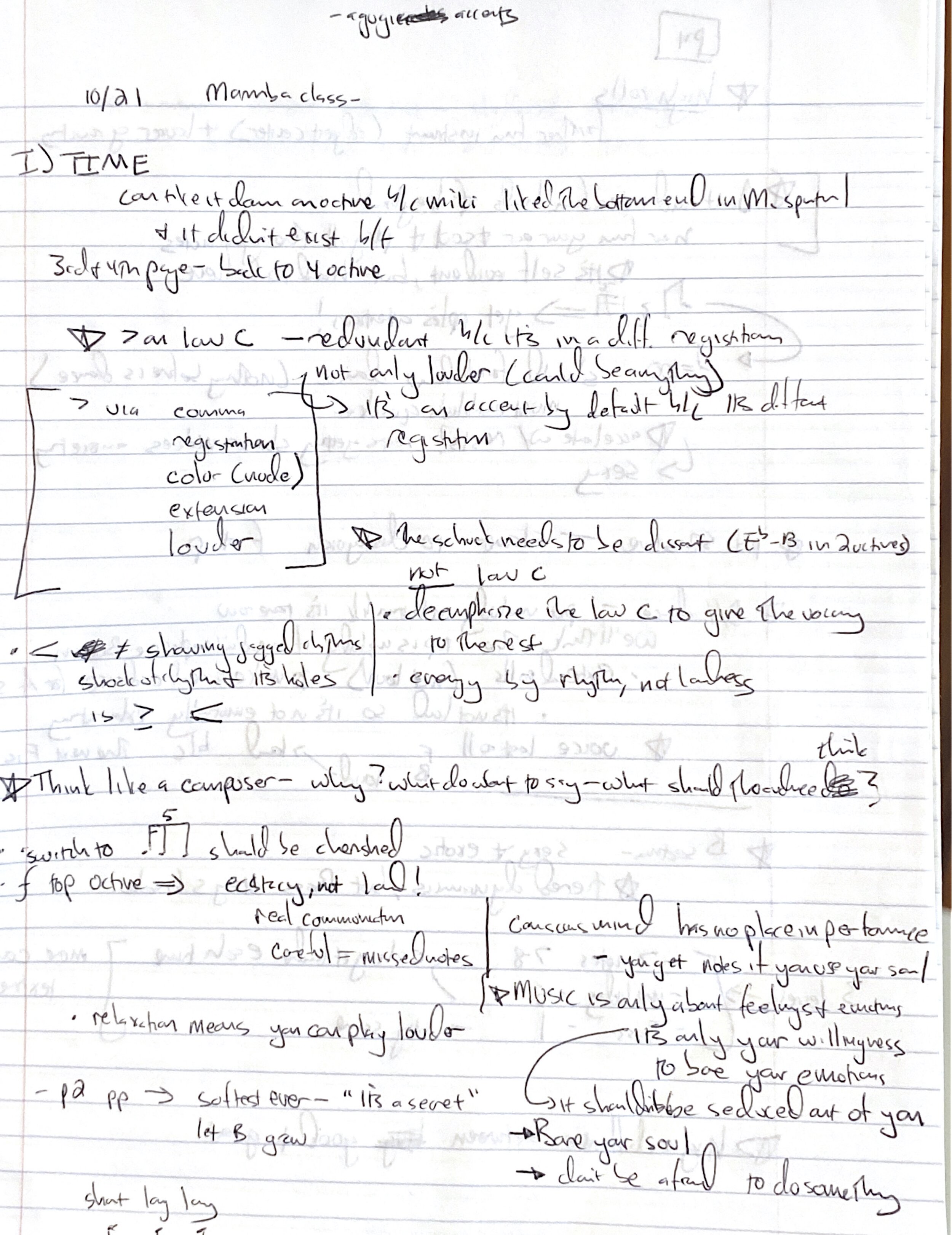

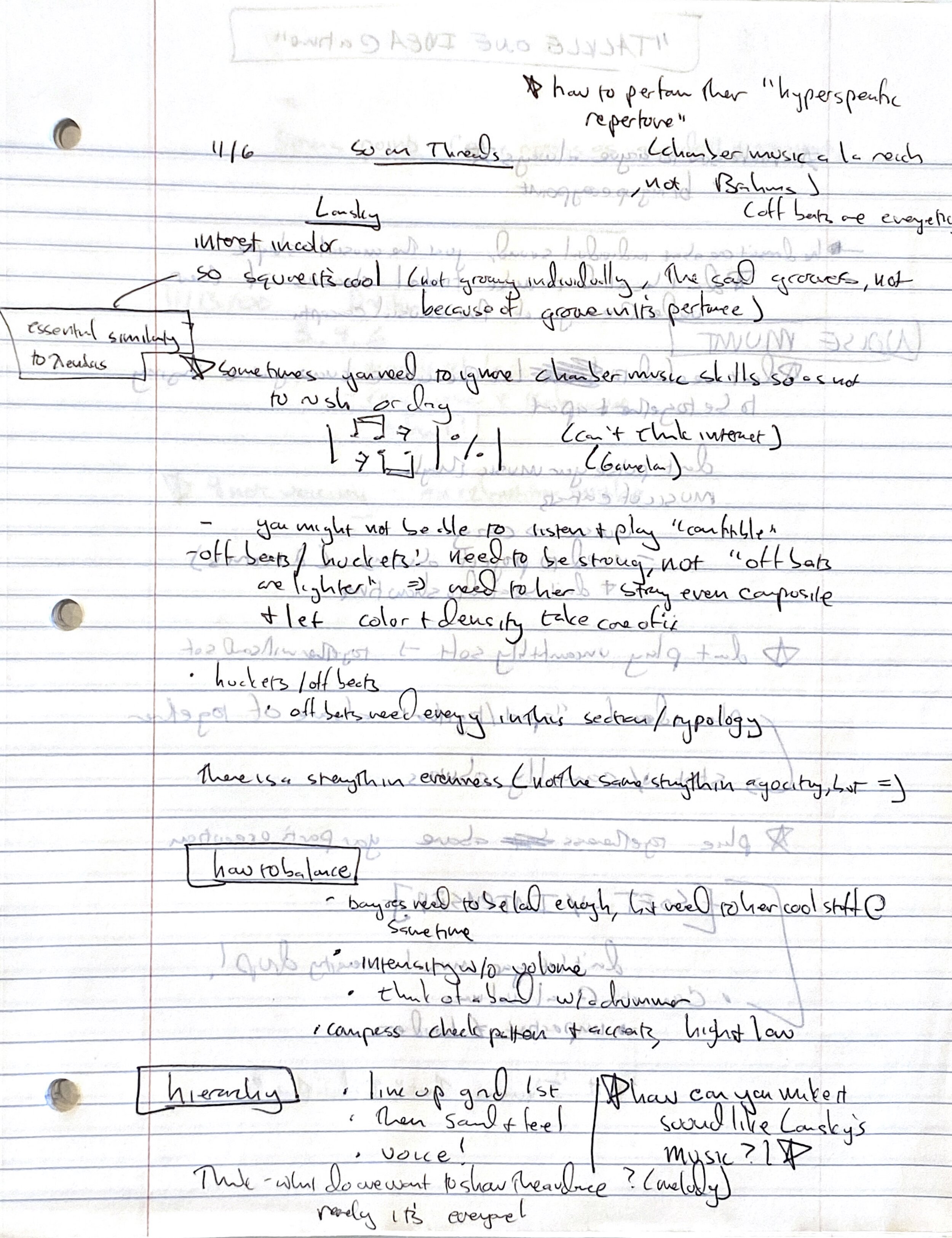

Here’s a summary from a lesson I took as a freshman at Peabody on Minoru Miki’s Time for Marimba, and on a coaching of Paul Lansky’s Threads. In both cases, In both cases, I tried to both summarize what happened in the lesson and provide some higher level organization of the more free-flowing events. Almost 20 years later, I have almost no problem remembering this content, although I still can’t read my own handwriting.

Then:

Assess your ability to change in the moment: were you doing what the teacher asked? Many times we think we’re making a concrete change, but our emotional biases blind us. Hearing the recording may explain why your teacher consistently asks for the same changes over and over and over.

Synthesis

Make a list of your key takeaways from the encounter. These ideas should focus your future practicing. Similarly, make sure to mark your music in accordance with the content of the lesson. Stickings, character markings, anything that you didn’t have time to mark in the lesson should make their way to your music. I recommend this step even if you think you’ll remember everything. On the one hand, multi-modal learning is essential for durable knowledge. On the other hand, studies show that our memory fades much more quickly than our perception of our memory. In other words, write it down!

Application

Create goals around your key takeaways, trying to make note of everything your teacher said. Great students don’t need assignments from teachers. One lesson should be enough content for weeks of work. My key takeaways from Jason Haaheim’s visit to KU “Great students bring problems to diagnose, not mysteries to solve.“ Your lesson recording should help you to try everything you can to make own your learning.

Practice Sessions: Ingestion

Goals: Get closer to your mental representation while prototyping methods of developing mental representation

How-To:

Pick a spot to work on, starting with smaller spans. Record yourself. Listen three to four times and make smart notes. I listen first for musicianship, and other big picture ideas, then for timing, then for intonation or tone quality, and finally for accuracy. Broadly speaking, I proceed along 2 paths from this point.

Option A

If you have a clear idea of what this passage should sound like, check your recording against your mental representation. Give yourself specific, detailed notes. “It sounds bad” is both poor grammar and poor analysis. “Eb in measure 5 is sharp,” or “consistently missing jumps between a 2nd and an octave in measure 2” is better, but still not great grammatically.

Then, make a smart, quick, repair, tackling one issue, using every practice technique you can think of.

Option B

What if you don’t know what’s wrong? You hit all the right notes, but something sounds off. If you don’t have one for this passage, but know something is not quite right, proceed with Option B, which is influenced by Design Thinking:

Brainstorm potential issues. Prototype a variety of changes, interpretations, or other variants. Try these quickly, and assess the effects. Perhaps inventing some exercises around the musical material can help focus your ears and hands? Then, proceed, circling back to option A.

Practice Sessions: Incubation

Goals: Refine your interpretation, combat stage fright by practicing performing.

How-To:

Choose a medium-sized chunk of music. Record yourself, and listen back, making specific comments on trouble issues. Categorize these problems: are these randomized occurrences or consistent? Small things (missed notes, bad transition), or systemic—a lack of dynamic contrast or tendency to compress fast passages? Make notes on the limits of your dynamics, tempi, character. Are they too narrow, too wide? Is your timing perfect?

Make a change, using the techniques outlined above. Tackle consistent issues first, then think about the larger issues.

I like to record in the medium scale because it helps me tackle performance anxiety. When we practice, our goal is to think critically about our own playing, diagnosing issues and planning our next steps. When we practice, that immediate feedback is a recipe for disaster. We can hone our performative skills by putting ourselves into “performance” mode, knowing we have our recording to help my critical thinking later. Over time, one can quickly enter this reflexive performance mode more readily. On this point, using a medium sized chunk is essential. Too often we practice our performance skills by making full runs of pieces. This is akin to jumping from a warmup to a marathon, with no smaller races in between. Not a great idea.

Performance Review

Goals:

Compare your memory of a performance to how it actually sounded.

Learn how to account for acoustics: timing, timbre, instrument choice

Refine the effectiveness of your portrayal

How-To:

Listen back to a concert performance, comparing your memories of the event to the recording. Does it sound the way you imagined? If not, what is different? Orchestral players will frequently use their colleagues or recordings to help hone their sound in different acoustics, calibrating their sense of their sound up close with the reality from hundreds of feet away. In chamber music, I find listening to a performance at a later date can help me calibrate my interpretations: did that moment land the way I wanted it to, or was my inflection too small for the space?

Some other recording situations worth mentioning:

Recording as Object

Goals:

Practice making a recording

Hone the skills of being a studio musician

Develop recording and editing skills

In recording studios, small scale inflections are less important, and larger consistency is more important. We can’t hear tiny details that really speak in live performance, but we do hear errors in timing and consistency, especially with percussion instruments.

Recording sessions are tiring, and have unique energy flows: long periods of low activity pierced by bursts of high-concentration. Why not become accustomed to this pacing by making a recording of a piece you know fairly well?

Similarly, making a demo recording can help you develop the skills of tracking and editing a piece. If you’ve been using recording in your practice, you’ve built up some technique within your DAW. By building upon the technological foundation you’ve developed in recording your practice sessions over a long period of time, you can put your new skills to work!

What to Do With the Recordings?

When Jason Haaheim visited KU, he shared his computer desktop with the percussion studio for a Powerpoint presentation. As his curser careened across his desktop to click “start slide show” (BTW, there’s a keyboard shortcut for this!), we messy, disorganized onlookers glimpsed the Jedi Archives: a perfectly organized database of excerpt recordings. I was in awe. Wouldn’t it be great to have everything I had ever played in one place?

This was ALMOST the moment!

My conclusion is: not really.

Although I do have a record (recorded or written) of almost every lesson I have ever taken, I treat my practice room recordings like post-it’s: a temporary memory aid whose value diminishes as its number increases. A desk full of Post-it’s is worse than no Post-it’s at all.

Why?

Similarly, I believe that I want to create what David Epstein calls ”wicked” learning environments (see last week’s post) when I practice, testing myself to remember what I was doing and how at precisely the moment that recall is challenging. Thus, my recordings often sound terrible.

The larger reason that my practice recordings are not valuable to me as documents, though, has to do with my larger goal in practicing. And they are not important to me as documents, since I believe in preparing to play something in infinite different ways, not honing in on one interpretation

I’d love to hear how you use recording in your practice routine. In the meantime, happy analyzing!